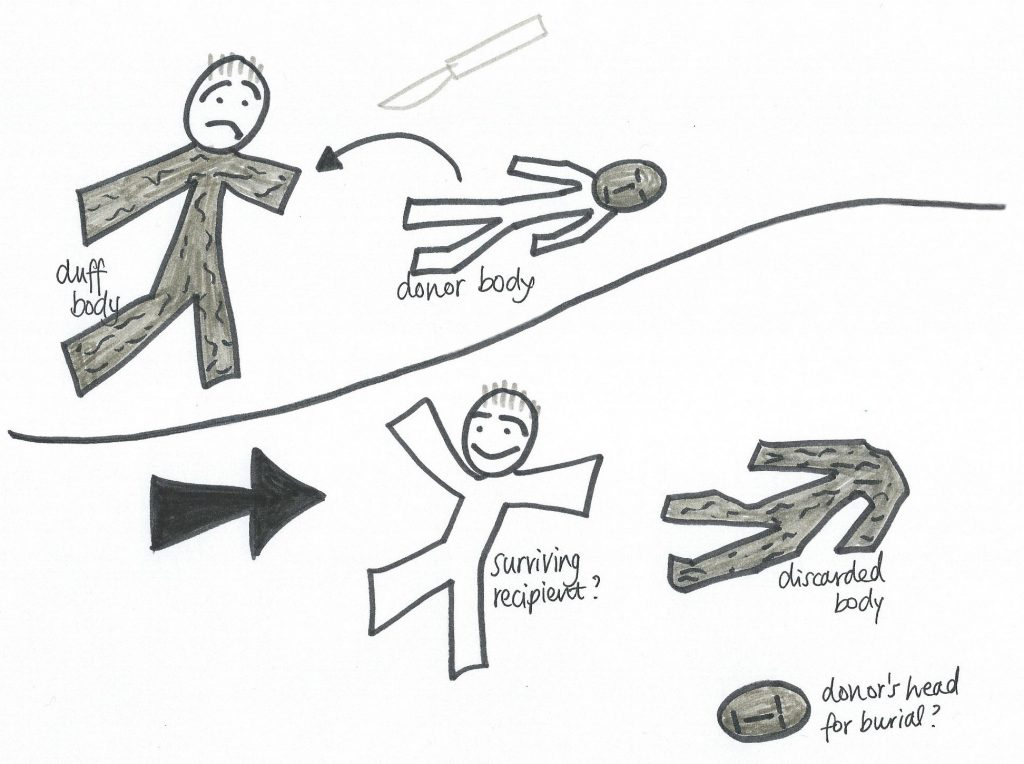

Dr Sergio Canavero wants to transplant a head from one human body rendered hopeless by disease onto another human body, provided by a dead but otherwise healthy donor.

This is not strictly speaking, as he likes to call it, a head transplant. Rather, it is a body transplant. It would be a head transplant only if you considered that the body was where the person principally resided, and that the head was a new part for the body to receive.

Okay, so you may consider some people to be more body than brain, but let’s stick to the issues. Only on a purely immunological level can the head be considered a new part for the body to receive. In other words, a new part for the body to reject.

What is really happening is that the person, principally residing in the head, is being given the body of someone else: a body transplant.

Small challenges

And if you thought relationships between body and mind were big issues, body transplants are a whole new world of conflict between the two.

The small challenges stopping Dr Canavero so far are largely twofold: technical and, yes, immunological. The technical expertise is needed to avoid the head dying in the surgical time between the point of severance from the duff body – including a clean slice through the spinal cord – and the point of successful connection to the new body.

The operation would have to keep an eye on the 45-minute mark between these two points – a deadline that is fine as long as the head is kept cool enough to withstand having no body attached to it for that long.

If attachment is successful, the body must then be quelled in its attempt to mount a seek-and-destroy immune attack against the new head.

Crazy spectacle

But perhaps I am wrong, and these technical and immunological challenges are trivial. After all, with enough money, will and persistent trial-and-error science has succeeded in splitting the atom, landing us on the moon and cloning Dolly the sheep.

To really hold Dr Canavero back, the ethical questions are all that will remain in the end. Except that if he is mad enough to do it, there will be someone desperate enough to want it, and some place somewhere ready to host the crazy spectacle – somehow convinced that the risks will be outweighed by the benefits.

But money and fame for a surgeon (and his sponsors and host) must not factor too heavily in the calculation of ‘benefits’.

And even with that sort of dilemma taken care of in an extremely complex risk-benefit ratio, the (I assume) sincere but wild dreams of one doctor to improve the lot of people with heads trapped on functionally dead bodies cannot be the only dreams that count. The potential nightmares for these people, plus the metaphorical ones for us all, need due weight too.

If ethical go-ahead did follow technical feasibility (two very big ifs), could we hope that the boundaries of the precedent were tight enough to dash any wider expectations that new bodies donated by the brain-dead could be ordered up for relatively trivial reasons?

There is not much distance, too, from such ideas to that of swapping out, for example, a selected person’s brain riddled with Alzheimer’s for the freshly deceased but otherwise healthy brain of someone else. Sorry, that is a slightly hysterical alarm call, because it is actually a rather long distance to this idea – when the person principally resides in the head and Dr Canavero’s dream of a head transplant is actually that of a body transplant. Yet the idea of ‘brain transplants’ nonetheless alarms us all.

Thankfully, the future for meeting modern demands for new bodies in extreme cases is far more likely to be sustained by numerous other options. Perhaps even the most desperate option would become more widely allowable, too: if there could be sound, unbreakable means of safeguarding individuals’ considerations for euthanasia.

For new bodies, though, Dr Canavero’s particular notion cannot be sustained, let alone sustained with any fairness. This lack of feasibility in the idea will remain, as will the ethical dangers, even if his multimillion pound theatre slot could be genuinely successful, and let alone if it could be replicated.

The body problems desperately seeking such solutions are instead far more likely to be resolved by the concepts of cloning and engineering tissues and organs, and by the advances in nanomedicine, materials, and so on. Perhaps humanlike robot bodies will be developed for human heads, Doctor Who-style.

And we’ll look back at that fun moment when ‘head’ transplants were once entertained and maybe even attempted.

Dr Canavero’s intention was the subject of one of the end-of-year round-ups, with a dash of medical news analysis, I wrote for medicalnewstoday.com.

You can hear my interview with a surgeon who pioneered face transplantation all the way back in 2007. I recorded an interview with the clinical psychologist working with him, too.

Originally published on 29 December 2015

Copyright © by Markus MacGill, 2015-2026. All rights reserved.